Able Seacat

Pet news while the world burns

I promised an account of Able Seaman Simon, hero of HMS Amethyst. I’d like this to be a newsletter about really important things, like why the Metropolitan Police didn’t notice that a man called The Rapist (Wayne Couzens) or a man called Bastard Dave might warrant some further attention and also prosecution. Or why Nicola Sturgeon is so spectacularly predictable: her appalling Gender Recognition Reform (Scotland) Bill, also known by anyone who can see sense as a licence for men to have access to women’s and girls’ spaces, should have been subtitled “Going up against the UK government in the name of Scottish nationalism” act, because as well as being a godawful assault on the safety of women and girls, that’s what it is.

Hang on I’d better set out my stall here.

Not all trans people are predators.

Hardly any trans people are predators.

But a predator can get a long way with his predation by pretending to be a trans woman. No better place to commit a crime than at sea; no better way to abuse women and girls probably with impunity than to be a man who notices how useful it is to pretend to be a woman. See, prisoners, often in for sexual assault, suddenly finding that they are women after all and being put in women’s prisons. Men in women’s refuges. Don’t get me started on men in women’s sports.

I used to rate Nicola Sturgeon, but mostly because of how she acted like an adult during the Covid-19 pandemic (that sounds like I think Covid-19 is a historical fact but I don’t). It was such a low bar though: my cat could look good compared to Boris Johnson.

Cats. Back to cats. This edition of my rambling will be menopause-free except to say this: I’m still fighting my hormones and my hormones are winning. So writing about heroic cats is the best I can manage for now.

Able Seaman Simon

He was born in Hong Kong, in an armaments store, just after the end of the second world war. He was mostly black, with a white muzzle and chest blaze. Black cats aren’t good luck on board ships, along with women, priests, whistling, and the words “rabbit,” or “pig.” His brothers and sisters all easily got jobs as rat-catchers on ships. Simon lingered. But his pedigree was good: he came from a long line of ships’ cats, and he was smart, showing affection to a visiting naval captain named Griffiths, of the British naval frigate HMS Amethyst. Simon became the captain’s cat, sometimes sitting on the captain’s cap. I like the detail that he would always sit on a chart when a course was being plotted. This will sound familiar to any writer who has had to remove a cat from their keyboard. And then remove her again. Keyboard, yoga mat, kitchen table while you’re using it for baking. They’re all the same to my cat.

Captain Griffiths was reassigned but Simon stayed with the ship, now curling up on the cap of the new captain, Bernard Skinner.

HMS Amethyst, a British naval frigate, was ordered to sail up from Shanghai up the Yangtze River to Nanking. There, she would replace another ship as guardian ship for the British Embassy, but also to transport fleeing British nationals if necessary. It was 1949, and China was at war with itself. Nationalists, the Kuonmintang, were fighting Mao’s Communists. It was a delicate job. The UK had a policy of non-intervention in China’s war (I will not call it a civil war because civil wars never are and someone should really come up with a better name for them.)

From Hansard, an account given to the House by the First Lord of the Admiralty.

On this occasion the object of the passage of H.M.S. "Amethyst" was to relieve H.M.S. "Consort" at Nanking. Opposing Chinese forces had been massed along the banks of the Yangtse for a considerable time and there were repeated rumours for some weeks that the Communists were about to cross the river. […]Thus early on Tuesday, April 19, the frigate H.M.S. "Amethyst" (Lieutenant-Commander Skinner) sailed f r o m Shanghai for Nanking, wearing the White Ensign and the Union Jack and with the Union Jack painted on her hull. When "Amethyst" reached a point on the Yangtse River some sixty miles from Nanking, at about nine o'clock, Chinese time, in the morning of the 20th, she came under heavy fire from batteries on the north bank, suffered considerable damage and casualties and eventually grounded on Rose Island. After this, the captain decided to land about sixty of her crew, including her wounded, who got ashore by swimming or in sampans, being shelled and machine-gunned as they did so. We know that a large proportion have, with Chinese help, arrived at Shanghai.

Amethyst fled downstream, away from the firing zone, and ran aground.

At about two o'clock in the morning of the 21st, the "Amethyst" succeeded in refloating herself by her own efforts and anchored two miles above Rose Island. She could go no further, as her chart was destroyed. Her hull was holed in several places, her captain severely wounded, her first lieutenant wounded, and her doctor killed. There were only four unwounded officers left, and one telegraphist to carry out all wireless communications.

No, First Sea Lord, you forgot a member of the crew. Able Seaman Simon survived, but only just. Under the onslaught, he had done what cats do and run for cover. But shrapnel hit him in the leg and back. His whiskers were burned away. But he managed to get to a dark hiding place and stayed there for several days.

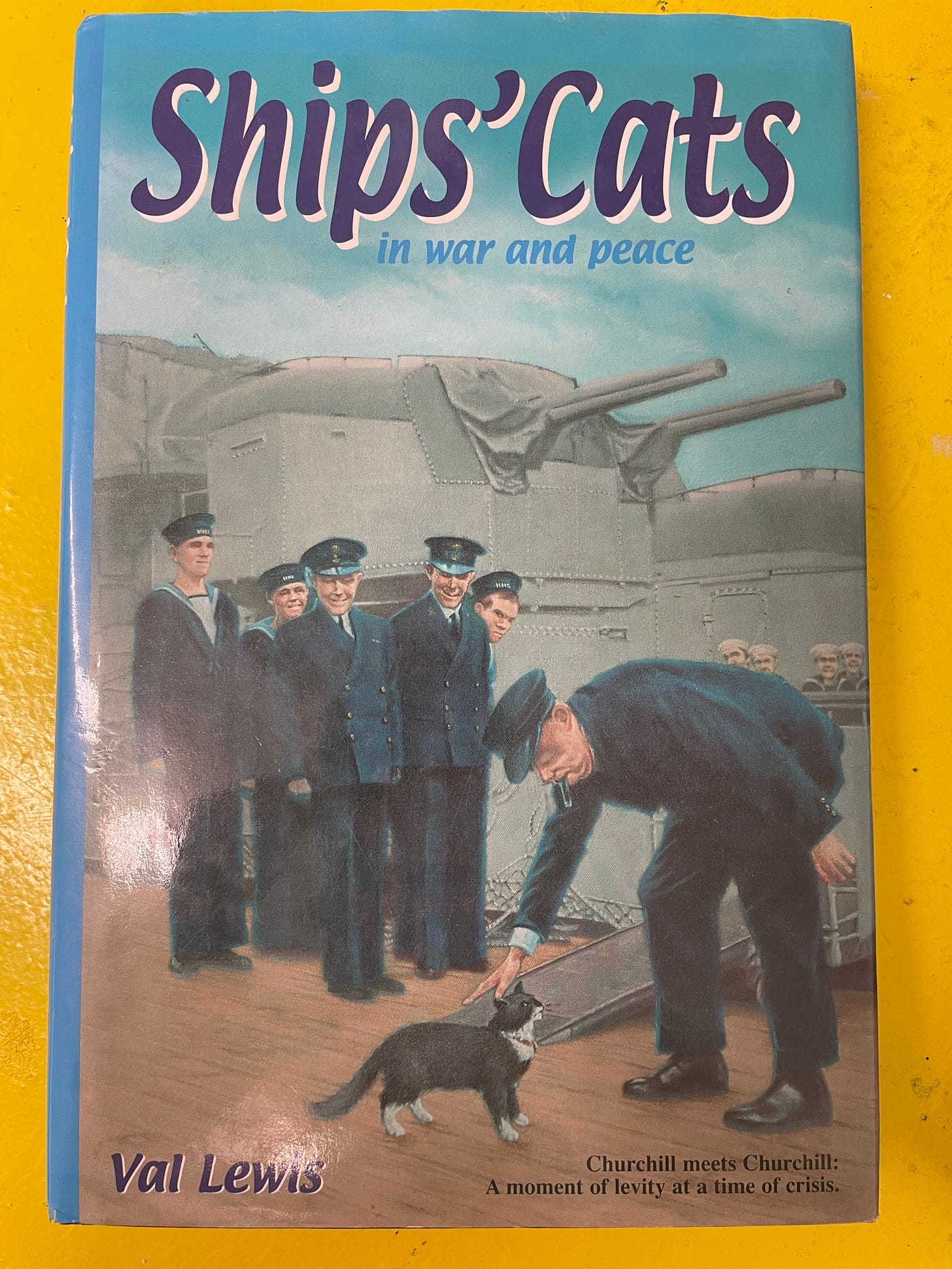

Here I quote the excellent book Ships’ Cats in war and peace, by Val Lewis. It is one of my most treasured maritime books, of which I still have a limited pile. When I finish writing a book, I give some of my research books away, but I keep the ones I like. From Nine Pints, I’m definitely keeping the one on vampire and corpse medicine. From Ninety Percent, I’ve kept Ships’ Cats, a wartime book of ships’ recipes and A Pictorial History of the Seamen’s Church Institute.

Back to Simon. Because he was a member of the crew, he was entitled to medical assistance. Flight-Lieutenant Michael Fearnley, medical officer, examined Simon in the sick bay. I think back to the sick bay on the Portuguese frigate Vasco da Gama, that I sailed on in 2011 because I was researching piracy and the Vasco da Gama had been hunting pirates. Yes, I see the irony. (Look up Vasco da Gama.)

I was well acquainted with Vasco da Gama’s sick bay because I was sleeping in it: there was no other accommodation on board, so I had one of two bunks in the small hospital section, which consisted of a bathroom, an examining room and the bunk room. I remember that the steel bath in the bathroom was full of gunk and feathers, because the crew had just given someone their ceremony for crossing the Equator, which on ships usually involves glue, feathers, gunk and stuff. The examining room was astonishing: proper hospital standard and certainly better than the corridors that now serve as examining rooms in hospitals, to the appalling consternation of their overworked and demoralised staff. I doubt Amethyst’s sick bay was as good as Vasco da Gama’s. I bet though that the officers’ manners were as good as those on Vasco da Gama, where I once watched with astonishment as an officer peeled an orange in one piece with a knife and fork, then told me they had been required to learn this at naval academy. I compared this — along with the bottle of red wine that was served at every meal because, well, they were Portuguese — to the officers’ saloon on Maersk Kendal, the container ship I travelled on for five weeks the previous year, where the captain was apopletic that the company had told him his crew should use kitchen roll not napkins. Such small things but the captain rightly saw bigger things being said with such thoughtless penny pinching.

The officers’ mess on Maersk Kendal, with kitchen roll. My seat was under the Queen.

Simon recovered, even with his singed whiskers, and was present when the Chinese Communists invited officers to come ashore to negotiate Amethyst’s release. It was an interesting negotiation. You fired first, said the Communists. We most certainly did not, said the British. Safe passage was not given. For three months, the Amethyst was stuck. This of course is nothing when you consider that during Covid, seafarers were stuck on idle ships for 18 months, not allowed to come ashore. It took over a year for the UN General Assembly to pass a resolution stating that seafarers were key workers, and therefore allowing them more rights if “rights” in this case meant being anywhere except the ship, and eating anything but ships’ stores.

Simon was busy. As well as catching rats, he was used as a therapy cat by the medic, who, as Val Lewis writes, “encouraged the wounded cat to sit on the end of their bunks, or even on their chests, where he would knead away with his paws, purring contentedly.” But the ship’s imprisonment dragged on, and there was no sign of thawing from the Communists (who did not yet control the country but they did control the 120 miles of Yangtze river that was the escape route). Finally, running low on fuel, Amethyst did a heroic night flit, if steaming 120 miles can be called a flit.

They succeeded. The next day, there was a ceremony on deck, with an announcement that,

Able Seaman Simon, for distinguished and meritorious service to HMS Amethyst, you are hereby awarded the Amethyst Campaign Ribbon. Be it known that on 26 April 1949, though recovering from wounds, when HMS Amethyst was standing by off Rose Bay, you did single-handedly and unarmed stalk down and destroy Mao Tse-Tun, a rat guilty of raiding food supplies that were critically short. Be it further known that from 22 April to 1 August you did rid HMS Amethyst of pestilence and vermin with unrelenting faithfulness.

When Amethyst with Simon returned to the UK, Simon became a celebrity. The cat who escaped China. The cat with no whiskers. The cat who dispatched rats and purred to wounded seamen and was equally talented at both. On August 22, 1949, the Yorkshire Post ran a small article headlined Simon of the Amethyst.

The Admiralty has agreed to the suggestion Our Dumb Friends' League that Simon, ship's cat of the Amethyst, should bedecorated, and has consented to the award the League's Blue Cross Medal.

The what league now? You may as well hold up that phrase and shout “INTERNET WORMHOLE” at me. In most contemporary accounts of Simon, he is awarded the Blue Cross medal by the Blue Cross. Ah but look here on the Blue Cross history page. “1897: A group of animal lovers founded Our Dumb Friends League – the original name for Blue Cross – to care for working horses on the streets of London. Their mission was to encourage kindness towards animals. The phrase "dumb friends" is thought to have come from a speech given by Queen Victoria.”

And in 1901, “We distributed horse sun hats on loan to make sure that the capital's horses were kept cool. Our hot weather advice is still some of our most popular.”

No, no, no, do not immediately google “horse sun hats” because you will end up on this Etsy page and have to look at images like this:

Able Seaman Simon — who was allowed the feline equivalent rank of Able Seacat, at least by the crew of the Amethyst and delighted journalists — did not get a sun hat, but he did get the Blue Cross Medal, and later the “animal VC,” the Dickin Medal. (A mongrel puppy adopted in 1938 by the crew of the Coast Guard cutter Campbell retired with honours after the war, rank Chief Petty Officer (K9C), Dog. One wartime cat was named U-Boat.) But he got the Dickin Medal posthumously, because while in quarantine, his health failed, he could not be cured, and he died aged two in November 1949. The newspapers reported his death with solemnity. And they should: for the love of an animal is a powerful crutch and especially in war. Those cats being carried by Ukrainian refugees; the endless pictures of cats on naval ships and fishing vessels, cuddled and held by fighters and hardy fishermen. As the Belfast Telegraph reported on December 1st, in a news article beneath one about a new rural water management scheme, “SIMON'S WOODEN COFFIN. AMETHYST CAT BURIED.”

Resting in a bed of cotton wool, his little wooden coffin draped in a Union Jack, Simon, the Amethyst cat, was buried at the P.D.S.A. cemetery at Ilford, London, this morning in grave 281, next to the resting place of a little 14-year-old dog named Teddy. Only Mrs. Grace Macrow, the cemetery supervisor, and two grave-diggers were present. Flowers sent by the public were placed on the grave and a temporary headstone was erected. Mrs. Macrow said: "We hope to get some timber from the Amethyst to erect a permanent headstone and we will have some of the crew here for a ceremony then."

When I travelled on Maersk Kendal in 2010, there were no cats. Rats were dealt with by rat-guards attached to the mooring ropes. But the spirit of Simon and every ship’s cat seemed to be alive, when an exhausted racing pigeon stopped to rest on the starboard bridge wing. I wrote this:

It has a ring on its leg so must be a racing pigeon, and I tell Marius about the pigeons of the Second World War who won medals for taking messages to important places. He says, “I’m going to stick a sticker on it to say it was on the Maersk Kendal and it cheated. It didn’t fly, it sailed.” The pigeon is an excitement. Really. Even the captain pays the pigeon attention. “We’re 40 miles out so it can’t go anywhere. It might get a scent around Lisbon or Gibraltar and try its luck.” He is not hopeful. Already it has a tray of water to drink from and a bowl of bread. Later it will have dried rice; split peas; dried foodstuffs in a variety that means affection. The pigeon also has a name: 4097430 BELG 2009. In less than 24 hours it has become the ship’s mascot

The Royal Navy banned cats on its ships in 1975. They were considered unhygienic. Possibly they are, but if hygiene is health, and a pet or mascot improves the mental health of men (mostly) who must spend months at sea, then the 1975 decision was a stupid one. I thoroughly enjoyed my five weeks at sea on Kendal, but I also know that being a passenger and being a working seafarer are like port and starboard. Different. I took this picture of the second officer on a day when he hadn’t seemed any more knackered than usual, but that is because he was always knackered. Two watches a day from 8-12 and work inbetween. Most of the crew ate their food in less than seven minutes so as to have more time for rest. I counted.

And this brings me to the International Transport Workers’ Federation Seafarers’ Trust. Last year, the trust asked me to be a judge on their annual photo competition, in which seafarers send in images they have taken. There were so many good pictures, and it was hard to choose between the final three. I did love this delightful image by Harold Papa Melendez, called “Cheerful Buddies,”

But in the end I and my fellow judges chose this.

Why? Because it is beautiful. The light coming in the cabin porthole, the tattoos, the clutter of his living space, the intentness of his gaze on his phone. For me it said huge amounts about life at sea in a deceptively simple image. It was taken by a Burmese seafarer, Able Seaman San Ko Oo, of a fellow AB who was talking to his family. He called his image “Home Sick,” (he separated “homesick” and I think I prefer it) and I wanted it to win because even now, even after the shipping industry has become slightly more visible than before, still too much is ignored about the people who bring us everything. They pay a high price for their decent salaries. That is, if they get their salaries: the ITF still has to fight to recover unpaid salaries: last year it was $37.5 million. See above: not everyone at sea is a criminal, but the best place to be a criminal is at sea.

I almost forgot.

Here’s Simon, in the arms of Sub-Lieutenant Monaghan, after their Yangtze escape. At least, that’s the caption, but Simon seems to have all his whiskers so maybe it’s wrong.

And Simon, just Simon, Simon of the Amethyst, Able Seaman Simon, Able Seacat, Simon VC, felis catus, 1947 (probably)-1949.

I love the story of Simon because it is about solace.

Solace: comfort or consolation in time of distress. From the Latin solari, to console.

That is the definition of the OED. But I think solace also means comfort or consolation in times of feeling alone, or homesick, or overloaded, or far from your family. I wish more ships had cats. The crew of Kendal would have found solace in a cat. (The pigeon flew away off Algeria, and when I tracked down its owner, a man in Belgium, he was entirely unmoved by my story. The pigeon never made it home.)

Finally, a video with no cats, pigeons or dogs in it. Just the seafarers who work at sea for months at a time, in all weathers, talking about the images they submitted, of their crewmates and friends, of their consolations and solace. It’s worth watching just to meet the people you never think about, though they brought you the computer or tablet or phone that you’re reading this on.

When Simon died, Petty Officer Frank, DSM (Distinguished Service Medal), told a reporter a valuable truth. “Simon was not just a cat. He was a friend.”

Next time: maybe some thoughts on being a fell runner who never wins anything but keeps on anyway. Keeping on keeping on. What else is there but that?