Cows

Swim, heifer, swim

I like cows. I like their calm demeanour, their curiosity. I also fear cows, because I am a runner and I know they are heavy huge animals who can move fast and squash me. I like cows, but I have never watched Cowspiracy or researched much about the dairy industry. I eat dairy products, though I don’t like milk. Cheese, yogurt, cream, OK. But milk, yuk. I’m not saying that makes sense.

Many years ago I met one of my mother’s fellow Rotary Club members. His name is Philip and he’s a dairy farmer. Many years ago I said to him, please can I come and watch you milking and he said yes of course. This conversation was repeated many times over the years and I never went. But now I am Keeping Busy, because my heart is not yet healed (not surprising considering how deeply it was wounded but god it’s a long haul), and when I saw Philip recently I asked him again, and he said politely, “you’ve said that before” and I got my phone out and said, “Wednesday?”

He agreed. He told me that his cows were milked twice a day and that I could go to the 3pm milking if I preferred. But I refused. If it’s to be proper milking it has to be bloody early. I woke up at 5 and drove to West Bretton. Philip’s farm backs on to the Yorkshire Sculpture Park. He rents some of their land, though he doesn’t put his cows on there any more because the park was worried that the cows would rub up against the Henry Moore sculpture too often. Now he just puts sheep on there because they can’t reach the sculpture.

I dunno, it is rubbed shiny by people anyway, why would cows make a difference?

Anyway I got to the farm at 5.50am. There was nobody around. I wondered around for a bit. Empty office. Empty milking parlour (it’s still called a milking parlour even now there are no milkmaids and it is highly modern and industrialized).

Finally a handsome man in a boiler-suit arrived, confirmed that he was expecting me, and asked if I had anything waterproof. I had, because Philip had warned me. I had the fishing oilskins/bib and braces that I’d bought and worn twice at sea, and wellies. Underneath my bright orange oilskins I had a bright pink running long-sleeved top, which I’d worn because it was long-sleeved and because Philip had said, “there’ll be all sorts flying around” but he hadn’t specified what the allsorts were.

Charles — the dishy farmer and Philip’s son — sent me back into the cow shed, where I found Philip, armed with a sweeping brush, who was verbally moving the cows towards the milking parlour. There was much shooing and gee-upping and other terminology probably particular to Philip and Home Farm. It worked. I stood by a gate while the cows passed and very much enjoyed their total bafflement at me.

This happened a dozen times. In you come, closer and closer, then SHIT NO SHE WANTS TO TOUCH ME and a swift retreat. I thought two things about these cows: they were very sweet, and their udders looked spectacularly uncomfortable. Some of the udders held FORTY LITRES of milk. Poor things. No wonder they like to be milked, or so Philip says. He also said they didn’t mind being indoors for ten months of the year. Sorry, what? They are indoors for as long as they are lactating. Then he told me when they give birth, they get to keep their calf for 24 hours and then it is taken away and housed in a pen.

Modern dairy breeding can sex the sperm, so 90 percent of cows born on Philip’s farm are female. The male calves are bred to be beef. I found all this shocking but did my best to look neutral. I eat cheese, I had no moral high ground here. Anyway said Philip, cows are lazy. They come in here and they just flop down. It’s not hard concrete, he said. “It’s like a Dunlopillow.”

The cows duly shooed, we went to the milking parlour. If I were a cow wanting revenge, I’d design a milking parlour exactly like this. The humans — two usually, dishy Charles and a surly assistant — are below the level of the cows. It’s like a garage inspection pit but you’re looking up the arse of a cow rather than a car.

There is no Witness-style old-fashioned milking going on here.

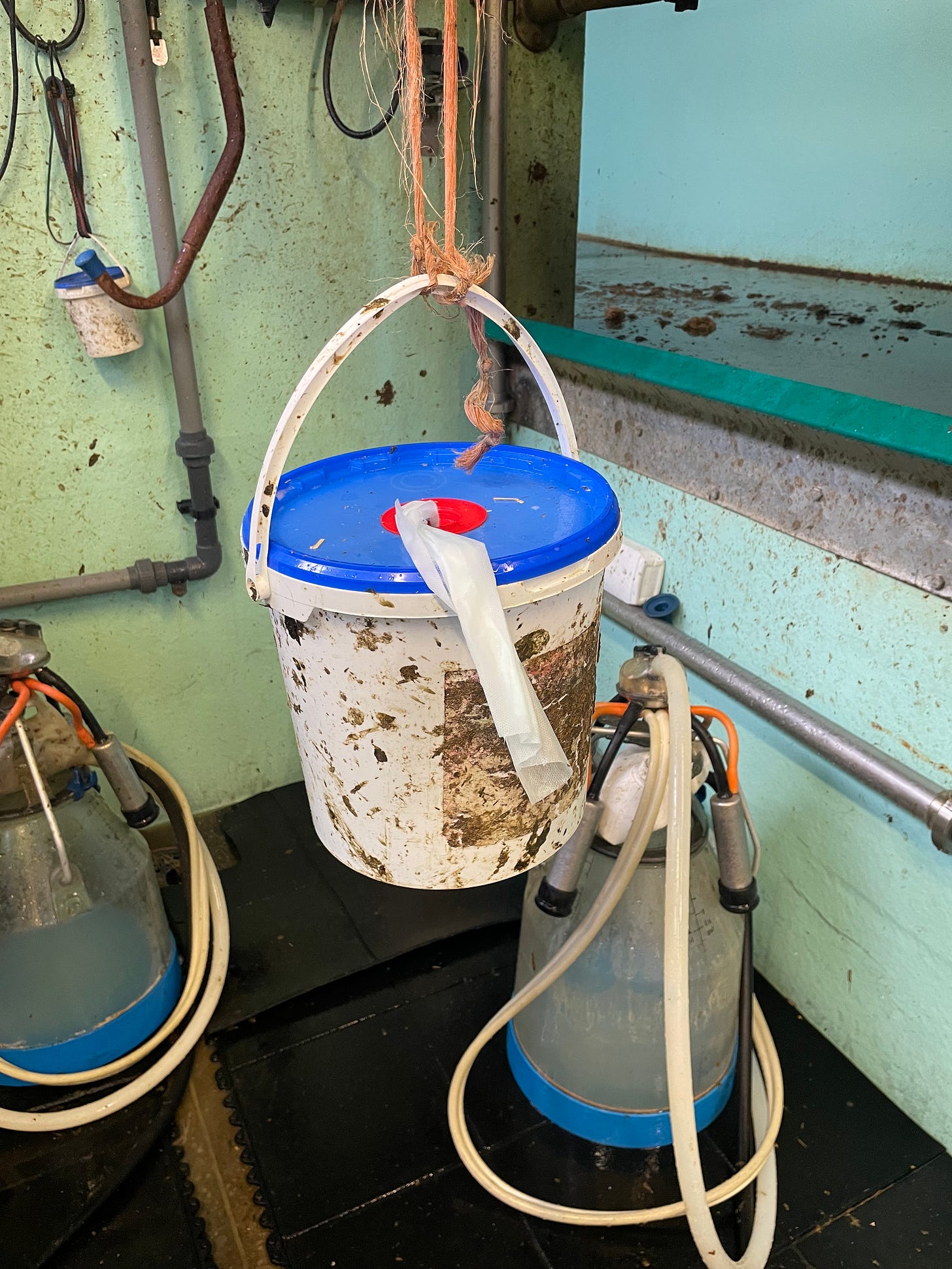

The cows are milked by devices called clusters, which vacuum-attach to their teats. Everything is measured digitally. The cows that are slow milkers get tape attached to their teats. This is important because there is only one set of clusters, and it switches between each side of the parlour. When one side is done, the other gets vacuum-milked. If a slow milker is opposite a slow milker, the whole system gets crippled.

Before the clusters are attached, either Charles or the surly assistant walks along with antibacterial wet wipes and wipes the teats. What a job. Teat-wiper. I did not join in. There wasn’t a lot of room and there was a lot to get out of the way of. Because the cows are not just there to be milked. They are there to lift up their tails and emit a vast green stream of shit, or an impressively powerful waterfall of yellow piss. Those two things are what Philip was talking about when he told me to wear waterproofs. Every thing that lives permanently in the milking parlour, like the container of wet wipes, is splattered with green shit.

So was I by the end of half an hour in there, and even though Charles valiantly tried to shelter me from one shit onslaught by stretching his arms out wide. My hero.

I couldn’t blame the cows. If I was having teats vacuum-milked, I’d take my revenge somehow too.

Each cow is branded with liquid nitrogen. This works as a bleach so it only works on black hide; if a cow is totally white they can only be tagged in the ear. Sometimes the ear tag doesn’t match the brand number. Why? Philip shrugs. Shit happens. Charles knows some cows by number, because they are the stompers. They always stomp at milking, always.

I think I would be a stomper.

The milk goes via pipes to a holding tank, where it is collected every two days by Longley Farm, and becomes my favourite yogurt.

After my time was done, Charles mentioned something. He looked at my bright orange oilskins and my bright pink top. He did not criticise. He just said, “we’re usually quite drab in here.” Right. Cows.

My running club recently had a discussion about the safety of running near cows. Some people have a proper phobia. Some are cautious. Philip was dismissive. “They can’t run as fast as you. They’re only curious. It’ll be reight.” But I know too many people who have been chased or intimidated by cows, so I’ll always be wary. I’d never run. I’d go nowhere bulls or bullocks. And I’d change my route if cows had calves (though Philip’s wouldn’t because theirs get removed). And I probably won’t wear bright orange and pink again.

What did I think about my morning of milking? I thought, animals are not ours but we act like they are. I thought, I wish they got to keep their calves. I thought, I still like Longley Farm yogurt.

Animal hero of the week : Sæunn the Cow

There aren’t many heroic cows in the annals of heroic animals. I’ve looked. I wrote about one here. That is also one of my favourite newsletters, about rain, because yesterday my soul was so, so black, and I walked 5 miles in the rain and felt slightly better. Rain always works.

You will cheer for Sæunn the Cow. In 1987, her name was Harpa.

She and two of her compatriots were being led to slaughter in the Westfjords village of Flateyri when she decided to take fate by the reins and make a daring escape. Rushing toward the sea, Sæunn flung herself into the fjord of Önundarfjörður and swam three kilometres across it. Many cows would have simply given up mid-swim or turned back around, but not her. Instead, she paddled on and, reaching the shore at Valþjófsdalur farm, was met by a friendly couple who rechristened her with a name befitting her feat (Sæunn, ‘sæ-’ meaning ‘sea’) and gave her safe haven for the rest of her days.

(I’m nicking this material from here.)

Because as we know from my book Ninety Percent, where I wrote about the sinking of a livestock transporter, and from that newsletter, cows can swim.

Not only was Sæunn a tenacious swimmer; she was pregnant.

To make the whole adventure even more narratively perfect, Sæunn gave birth to her calf on Sjómannadagur, the Fishermen’s Day holiday. Her calf was given an equally seaworthy name: Hafdís, or ‘Sea nymph.’

Stories of Sæunn’s exploits made her famous not only in Iceland, but also travelled as far as India. The couple who adopted Sæunn after her escape received letters from all over the world, thanking them for their kindness and sometimes including donations. (Conversely, the farmers in Flateyri were known to have received some threatening letters for having attempted to slaughter the cow.)

When Sæunn was old and dying, the farmer led her to the beach where she had arrived. She was buried with a view of the fjord. But she lives on as a picture-book called Sundkýrin Sæunn (‘Sæunn the Swimming Cow’). I love it when animals rise up. More like Sæunn please.

This is the bit where I politely urge you with Yorkshire grit to a) subscribe or b) upgrade to a paid subscription or c) click on the like button so I know you’ve read and maybe liked this.

Loved reading this! I have been to the Westfjords and can confirm everyone really does wear those jumpers. It’s the size of Wales and has a population of just over 7,000 people.