Fishes

Slimy things in the water

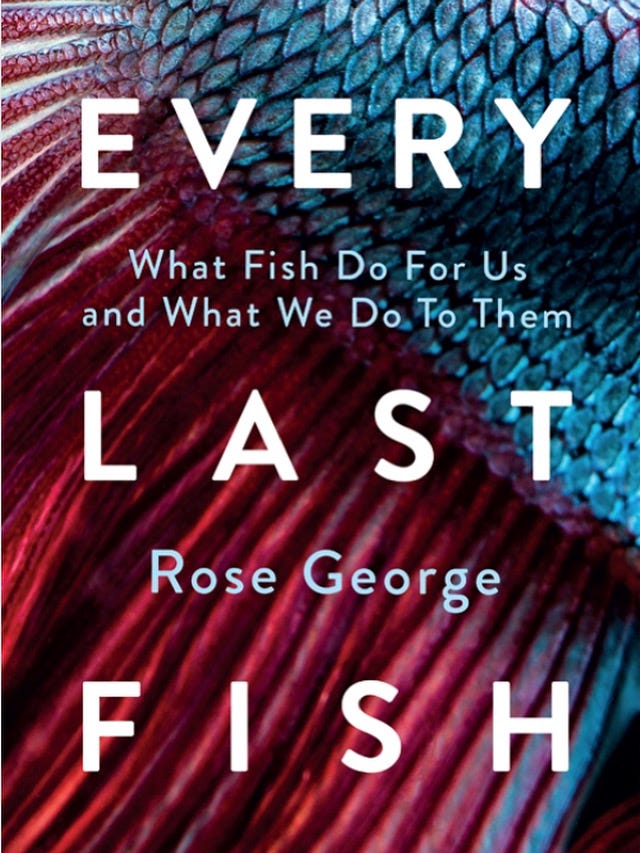

So I have a new book out.

I can’t quite believe that sentence, as it has taken me so damn long to write it. Every time I write a proposal for a new book, I promise it will be a quick one. And every time it takes at least five years from proposal to publication. This one was even better: six years. I can forgive myself a little as the writing of it coincided with a pandemic and a debilitating heartbreak, both of which added some difficulty. But even so. Six years.

Anyway. I did it, and I am extremely proud of having managed to pick myself up from deep grief, three months after my relationship was disintegrated (that is a deliberate tense), and rewriting the first draft, which had been flabby and had not sounded like me. I spent the month of June rewriting it, cutting 30,000 words and adding a new chapter, which was published last week as the Guardian’s Long Read:

Another chapter, on trawling with Captain Tom, was published in the Telegraph, with a stupidly politicized headline which I had nothing to do with.

I barely mentioned black fishing (this is when you land catch you’re not allowed to and pretend it’s something else), I didn’t write about EU boats, and I definitely didn’t write about the crushing of British fishermen. I mean, there are hardly any left to crush, for a start. The fishing industry is tiny: 0.03% of GDP. The biscuit industry is far greater and employs about ten times more people. But nobody is sending biscuit tins floating down the Thames and talking about bringing back British biscuits. The fishing industry is complex because its image has so little to do with its reality. But also because when we say “fishing industry,” it means a few different things. It means the inshore fishermen who are fishing mostly modestly and not generally causing much damage (except for the dredgers and bottom trawlers, which do). But it also means the fishing barons: the companies who own most of the quota and who earn most of the money, and do not want any restrictions on their unfettered access to the fishes of the ocean.

Oh yes.

Fishes.

I very rarely read the comments under any journalism I write these days. But last week was the launch party of Every Last Fish at Daunt Books in Holland Park.

There are two Daunt Books not far apart in west London , and one was hosting a reception by the Ginger Pig, a butcher’s, and one was for me. Plenty of people got confused, including some friends of mine who went to the wrong bookshop and were pleased to be given sausage rolls but also quite puzzled. Ginger Pig people came to my launch and were equally puzzled not to be given pork pies. But it all settled in the end, and Granta put on a lovely launch, and my wonderful editor Laura brought me a bag full of lovely fish and cat-themed presents (we both have cats), and plenty of people came and it was good.

The point of that diversion was that my old friend Ross came, and he works at the Telegraph and had read the extract and he had a smile on his face when he said, “you should read the comments.”

So I did. I went straight from London to a mini-book tour in Cornwall, in Penzance at the Edge of the World bookshop and then to the Falmouth book festival. I had a LOT of time on trains and plenty of time to read the comments. And oh my goodness. I thought, having written journalism for 30 years, that I had probably encountered most things that rile people. No. Several commenters were apoplectic. About what? That I think the fishing industry needs to be fettered if we are to save the ocean? Or that the current economic model of seafood, where we export 80% of fish that is landed by UK boats and import 80% of what we eat, is NUTS?

No.

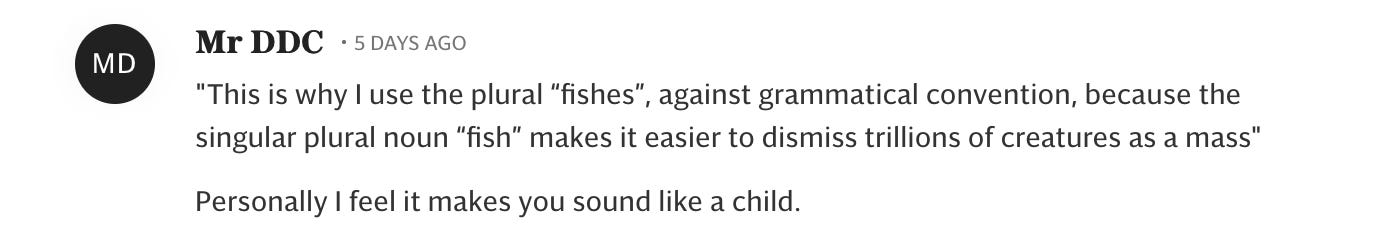

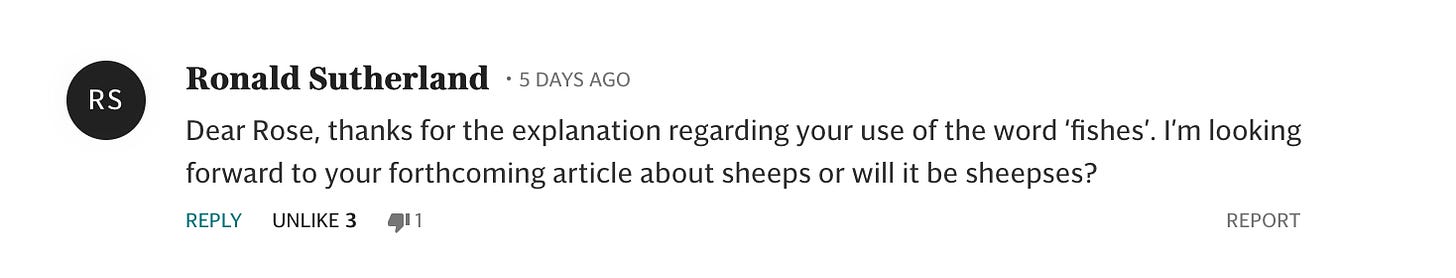

They were furious that I had used the plural “fishes.”

Though some of the comments were funny. Yes, I am now working on a book about cattles.

And I know you should never respond but I made an exception.

—

Book festivals and bookshop events are probably my favourite part of writing books. You usually get to meet nice people who think you are interesting enough that they have actually spend money to hear you speak. You get interviewed by interesting people too. In Penzance, I was interviewed by Rachel, the owner of Edge of the World bookshop. Captain Tom turned up late. He later apologised and said his stylist had delayed him. I said, nothing like making an entrance. It was a little odd talking about going out trawling when the person you went trawling with is three feet away in the front row. But it was a good crowd, considering it was the day after publication, and I had fun.

Then to Falmouth, a town about which I know nothing, and which I have left as a big fan. It’s lovely. I was interviewed there by Hugo Tagholm and honestly I had to do a bit of fan-girling, because Hugo used to be CEO of Surfers against Sewage, a group I admired enormously in my sanitation days and still do even though I’m no longer in my sanitation days (though increasingly thinking I should take a look at it all again). He’s now CEO of Oceana UK, a marine conservation group I highly respect and whose research I have relied on for Every Last Fish. I was told that Hugo often turns up in a wetsuit, but apparently that was in SAS days, and he was wearing a “SAVE OUR SEAS” jacket instead. Equally arresting but not so good for surfing.

Another reason that I really love appearing at book festivals is that you always meet people there who you really wish you had met before so you could have written about them.

Stunning Story Number One

In Penzance, my taxi driver was a man called Tony whose brother was a man called Ian who was known for singing sea shanties while driving clients around. But Ian was shopping at Tesco so I got Tony, and Tony was not super friendly at first. But we got talking, and then he told me that Ian had been skipper on the Margaret and William, a gillnetter that had been sunk by a chemical tanker in 1991.

Er, WHAT?

I looked it up.

The skipper — sea shanty Ian — and the first mate had been sitting in the wheelhouse, when the mate suddenly looked horrified. The skipper turned his head to see a wall of metal. The tanker went through the sleeping quarters, the skipper and mate were thrown into the sea. The supernumerary (a crew member without a specific job) managed to swim through the hole, then stayed under the tanker till it passed. The tanker carried on as if nothing had happened, because to its crew, nothing had.

Later, to the credit of the tanker skipper, the crew noticed paint streaks on the bow, and the master reported it to authorities. Investigations were done and it was concluded that the Jacobus Broere, a Dutch chemical tanker, had mown down the fishing boat and not noticed. Two men on the Margaret and William never escaped their bunks.

Here is the report.

Stunning Story Number Two

A woman in the audience at Falmouth took the microphone during the questions session. I thought she was one of the “this is more a statement than a question” types, but she wasn’t. She talked of Mexican marine reserves and how successful they had been, which is music to my ears as I believe strongly — and so do people far more expert than me — that if we can limit human activity in even 10% of the ocean, the positive effects will be felt far beyond that 10%. The sea can heal itself, but we have to let it. I can’t remember her question but she definitely had one.

Afterwards, she bought a book and as I was signing it for her she said, “I was rescued by a container ship at the age of 13.”

Er, WHAT?

Jenna — this is her name — came from a sailing family, and they were out at sea when a wave destroyed everything useful on the boat: radio, mast, everything. The hull was overturned but righted itself so she said, “we made good for four days,” which I assume is a sailing term for managing to survive the weather and the water and the shock. Finally a Chinese container ship passed and — remarkably but not that remarkably thankfully — stopped and offered help. “They asked us what we wanted and we said we wanted to be rescued.” They were taken aboard and when I asked if they were well fed, Jenna said she had counted five types of protein in one meal and after the rescue she turned vegetarian for a while.

Then she went on her way and I signed the next book.

My mini book-tour ended in Falmouth, I spent eight hours on trains getting back to Leeds, and next stop is Whitby Literature Festival on 9 November.

All upcoming events are listed — if I remember — on my website.

Animal heroes of the week

All the fishes.

All of them.

Treat them better.

Look, I’m not saying that if I’d been able to come to your launch I would somehow have sidled off to the Ginger Pig one instead, just that perhaps (as a longstanding fan of their sausage rolls and indeed their pork pies) I might have found a way of going to both. I am now going to click on buttons until I find I have bought your marvellous (and I know it will be marvellous) book about fisheseseseses.

I’ve been enjoying your book on Radio 4. Having grown up near Lowestoft and then gone to university in Aberdeen, fisher folk were part of my life. For several summers in the early 70s I worked in Aberdeen fish houses (the gutting apron has not changed since the 19th century) I learnt a great deal about life from the formidable fishwives. Thank you for documenting this world.