For heavens sake stop it

How a warrior sometimes looks like a poor old woman in rural India. Or a pigeon.

What does a toilet have to do with sex ?

A lot.

There are very few spaces that are meant to be secret and private. Yet a public toilet, or anything except a family toilet, is also public and accessible. I was once a judge on an architecture competition to design a women’s toilet for the developing world. I chose the winning design because of one thing: the exterior space had no corners. No corners for someone to hide behind, no corners for a woman or girl to feel nervous about. The walls curved, and it was shocking that this was considered innovative. This is why it is baffling that so many women in politics are so blasé about letting intact men into women’s toilets. Yes, not all men. But yes, some men. Those some men who will take any chink in security to exploit it, to be a predator.

So toilets have to do with sex because of two things: the sex of the person using it influences how safe they can be, and the sex that can be forced upon a vulnerable person using a toilet.

I’m writing about this because I read a quite astonishing BBC article yesterday, written by Soutik Biswas, which I wish had been headline news. It doesn’t involve toilets but the absence of them. In 2019, the Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi, who has made improving India’s awful sanitation a loudly promoted part of his prime ministerial mission, declared that all Indian villages were now Open Defecation Free. Here is how I described open defecation in my book The Big Necessity:

‘That’s where the toilet starts,’ Joe says, often, pointing to the side of a road just outside a village. I don’t need to specify which village, as only four per cent of the population of Orissa has a latrine, and the sanitation story is the same everywhere. Some- times, returning in the dusk, I play a safari game. There: an old man squatting down, his buttocks exposed. Over there: a woman who has stood up suddenly at the sight of a car, and hastily pulls down her sari, but her face is resigned, not embarrassed. Here: two men walking back companionably, each holding a plastic lota mug that contained the water they have used to clean themselves. This stand- ing up straight and the carrying of water vessels: these are the signs of the open defecator.

Every day, 200,000 tonnes of human faeces are deposited in India. I don’t mean that they are dealt with, or sent down sewers or given any treatment or containment. These 155,000 truckloads are left in the open to be trodden on, stepped over, lived among. It is a practice known as ‘open defecation’, and it is done on a scale, in the words of Sulabh International, that compares to ‘the entire European population sitting on their haunches from the Elbe in the east to the Pyrenees in the west’. Indians sit on their haunches from the deepest forest to the heart of the cities. They did it beside train tracks, as V.S. Naipaul recorded with disdain in 1964, and still do. The Indian journalist Chander Suta Dogra recently described an early-morning scene familiar to any train-traveller in India. ‘Right in your face are scores of bare bottoms doing what they must.’ Open defecation is so endemic, people do it even outside public toilets in the centre of a modern city. I see this one afternoon in the bustling city of Ahmedabad, where by early afternoon the pavement outside the toilet entrance is dotted with shit. I choose not to examine the interior.

I’d hope that that passage is completely out of date, and I’d like to believe Narendra Modi when he says that ODF India is now a reality. But I don’t think it is, and I don’t, partly because of that BBC story.

I once travelled to Bihar with the Great Wash Yatra, a travelling sanitation carnival. Yes, I’ve had quite a career. What I remember about Bihar is that we weren’t allowed outside the high school compound because en route one of the Yatra’s drivers had accidentally killed a pedestrian. And that for exercise all I could do was run around the high school compound, again and again and again. And that when the parade ground/stadium was constructed, the bamboo poles used to build it arrived on bullock carts. Bullock carts! When nearly every rural villager I had met, even in the poorest boondocks, had a smartphone.

Mind you, I never like the “there are more smartphones than toilets in India” comparison. It’s old, and it’s pointless. Of course there are more smartphones than toilets. You don’t have to maintain a smartphone, or clean it, or give up your land for it.

Bihar is beautiful, but much of it is spectacularly poor. So I was not surprised to read that a 12-year-old schoolgirl in Bihar was forced to go to a sugarcane field to defecate, because her family did not have a toilet. And I was not surprised to read that when she was there, she was raped. I was not surprised because this is not rare. What better for a rapist than a place that is sought out for its privacy and seclusion, where a woman or girl has to squat and be at her most vulnerable?

But I was surprised to read the rest: because that poor girl’s mother knew that her daughter had been raped by her schoolteacher, 39-year-old Niraj Modi. And although the schoolteacher’s father testified that his son had mysteriously quickly died, and produced pictures of his “dead” son under a pyre of wood, the mother didn’t believe it. She didn’t believe it because she lived in a village and she knew that in a village people know everything. And no-one had heard the rapist was dead.

So she went to the authorities, and she kept going. A poor and apparently powerless woman, who dared to go to the authorities, and the police, and defend a 12-year-old girl who probably counts amongst the least valued humans, certainly in the eyes of many village police and authorities. The mother went to court, she found evidence that he was not dead, she denounced him. And in October Niraj Modi gave himself up, was tried and sentenced to 14 years in prison.

What a woman. And what an amazing piece of reporting.

Animal hero of the week: Cher Ami

During the First World War, when technology advanced rapidly along with medicine (blood transfusions became almost normal, for a start), the military still relied on animals to assist in its battles. Horses, dogs, cats. And pigeons. The US Army Signal Corps had a troupe of 600 pigeons that were used for sending messages. I can probably run 7 miles in an hour on the flat with a chasing wind. A pigeon can fly fifty. Pigeons are extraordinary creatures and if you call them flying rats I’ll just point out that rats are also astonishingly clever and able and heroic. And with the exception of cockroaches, I like all “pests” because pests after all are the smartest because they survive the most despite everything we throw at them.

But what about radios? They were heavy and clunky and the wires were delicate and difficult to lay safely. A pigeon though: you just launch it and hope the Germans — who used their own birds and got used to shooting at pigeons with automatic weapons — missed at least some of them.

On October 2nd, 1918, 550 US soldiers got stuck. They had advanced into the Argonne forest in Belgium, and were trapped behind German lines. They became known — after the fact, I think — as the Lost Battalion. They weren’t lost. They knew exactly where they were, and that they had no radios. They were subject to punishing attacks from the German forces, and also from Americans, who bombarded the line they were bravely holding, by mistake, and killed thirty men. The commander, Major Charles Whittesley, sent out bird after bird over two days with increasingly desperate messages.

First bird: “Many wounded. We cannot evacuate.”

But the bird was shot down.

Second bird: “Men are suffering. Can support be sent?”

But the bird was shot down.

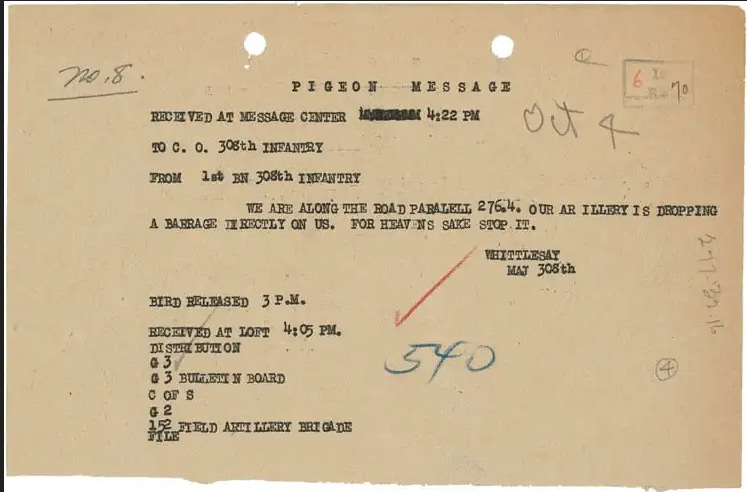

The Lost Battalion — actually the Stuck and F*cked Battalion — turned to Cher Ami, a male homing pigeon bred in England but donated to US troops. Cher Ami was, according to the Smithsonian Museum, “a registered Black Chock homing pigeon.” The message in the canister attached to his leg read:

We are along the road parallel to 276.4. Our own artillery is dropping a barrage directly on us. For heavens sake stop it.

Cher Ami launched, but the Germans saw him and opened fire. He was shot down but managed to take off again, his breast shot through and one leg severely damaged. Even so, he flew a mile a minute back to his loft at division headquarters, arriving either 25 minutes, 90 minutes or an hour and five minutes after he was launched, depending on which report you read. With that vital Pigeon Message, the Lost Battalion were saved, and army medics tried to save Cher Ami, who rallied enough to be put on a ship back to the US. He survived until the following June, but died at the age of one. Of course he was stuffed.

He was also awarded the Croix de Guerre, the Animals in War & Peace Medal of Bravery, and became not just a stuffed one-legged pigeon, but a poem, a children’s book, a novel and even starred — as himself — in an astonishing 1919 silent film about the Lost Battalion and its magnificent pigeon. Of the 550 men stuck on that hill, only 195 escaped unharmed. Some of those 195 starred as themselves in this film.

Post-script:

Many accounts of Cher Ami assume the pigeon was female. But for some reason, the “enduring mystery” according to the Times, of Cher Ami’s sex inspired some Smithsonian scientists to examine tissue from the pigeon’s leg, last year. Cher Ami was definitely a cock.