Next week’s newsletter and every newsletter from then on will be partially paywalled. Sorry: I don’t much like paywalls either. So please sign up for a paid subscription if you want the three course menu (including animal hero of the week). Reminder, there are signed copies of Nine Pints for the first X number of subscribers (it’s a moving target).

In a junk room in my house in France (yes I have a house in France because it was cheap and I am lucky and look you can rent it if you like), there is a garment made of sky-blue polyester. It was a gift from a woman in Afghanistan, which I visited in 2003, for all of eighteen hours. I can’t now remember how this started, but at some point I was invited by Jo Elvin, then editor of Glamour magazine, to come to her office, and I was then invited to visit Afghanistan to write about the lives of women. This was six months after the NATO had set up ISAF (the UN-mandated International Security Assistance Force). The trip, she said, was the idea of some policy people at Number 10 Downing Street: they wanted to show that the invasion had been worth it, that women’s lives had been vastly improved by NATO’s invasion, and they thought that one of the ways to do that was to get a feature in the biggest-selling women’s magazine of the day. In the waiting room at Glamour, there was another woman. I remember thinking, she looks intimidatingly stylish. I still think she is stylish, but Karen Robinson, excellent photographer, became a good friend and not at all intimidating, not least because of that slightly mad trip to Afghanistan.

I’ve done a lot in my career. I have been to many places, some beautiful, some weird, some horrible. Yet of all those trips, one always attracts people’s attention, and puzzlingly it’s not my 18 hours in Afghanistan. Yet I’m glad this is the case, because it’s how I met my friend Rhodri, who came up to me at a mutual friend’s birthday party and said, before he said hello, “did you go to Saddam Hussein’s birthday party?” I actually remember it as him barking “DID YOU GO TO SADDAM HUSSEIN’S BIRTHDAY PARTY” like a wartime film interrogator but he swears he didn’t shout. Or bark.

This happened again two weeks ago, when someone at East Street Arts, where I rent a studio space, came up and without barking, said with wonder, “did you really go to Saddam Hussein’s birthday party?” Yes, I replied. Twice. The question is followed by, “what was it like?” and I have a flippant answer ready. There was cake. It was green. It was shaped like a flower. I didn’t get to eat any.

Also, it was a mass gathering of terrified people, probably forced or as good as to march up and down a parade ground in Tikrit, Saddam’s home town, in front of a balcony-full of tubby men with black moustaches wearing dark green olive uniforms. I don’t remember much about the party except for seeing marching men in white flowing robes, and then being allowed to mix with the schoolgirls, and being delighted that they dared to talk to me in their “I am learning English” English despite the minders that accompanied us at all times.

I was in Iraq for ten days, twice. Yet I don’t think I understood much. Karen and I were meant to be in Afghanistan for two days, but the plane hit a luggage vehicle and we lost hours and had to divert. This meant that I made another lifelong friend by waking up the eminent journalist Robert Sam Anson in Karachi airport to tell him we were boarding.

I don’t think I understood much in Afghanistan, either. We were deposited at the British high commission in Kabul, a highly secured compound which seemed to be staffed entirely by men. I remember only that they seemed nonplussed and comically disappointed that two women from Glamour magazine looked so unglamorous. I also remember the official asking with bemusement, so what exactly do you want to do then? And me saying, “we want to visit beauty salons” and watching his face try to be as diplomatically unscornful as possible.

We wanted to visit beauty salons partly because Jo Elvin had given us bags full of cosmetics to distribute (and I was given a bag-full too which was embarrassingly exciting, as I am a woman who has never understood cosmetics enough to apply them properly and probably never will). And partly because beauty salons were one of the few places where women could speak freely with each other. Because women need single-sex spaces, don’t they, Nicola Sturgeon? We did visit beauty salons, and also a bakery for poor women to get on their feet again. We drove through Kabul and saw that there were chips for sale, and that most women still had burkas. We met Shukria Barakzai, who had run a secret school for girls during the (first) Taliban rule and also set up a newspaper, and who was strong and powerful and a delight.

Karen took this picture of a bride in the beauty salon. God knows where she is now.

I think it may have been our translator who gave me a burqa. She thought it was amusing.

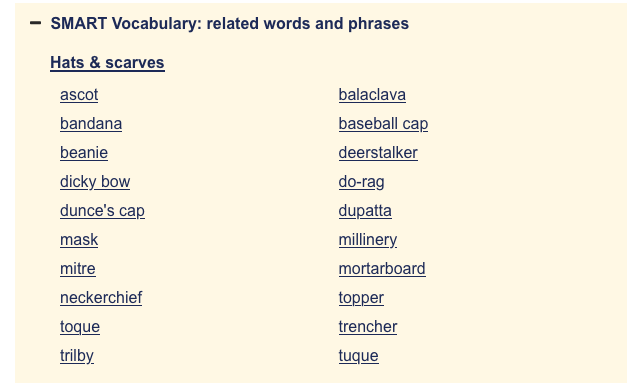

This is the list of similar items to a burqa according to the Cambridge English Dictionary.

Try on a burqa and you will quickly realise it is nothing like a mortarboard, or a beanie, or a bandana, or even a balaclava. It is to a hat as a T-Rex is to a newt. A balaclava is total freedom compared to a burqa, because you can see with it on. When I first tried on the burqa, I realised that not only is the burqa a hideous concept, but it is physically designed to be even worse than its concept. It was made of cheap polyester, which in Afghanistan’s warm months would seem unbearable. The grill over the eyes, awful in itself, quickly frayed, reducing my vision even more, because I could not get my hands up into the tight-fitting headpiece to pull the fraying threads out of my eyes. I could barely see in front of me and I had no peripheral vision. Mine was the “hands-free” version, stopping at the waist in the front so that at least you could freely use your arms. I thanked whoever gave me the gift, and I showed the burqa to a few people over the following few years, but then I was ashamed of it and threw it in the junk room, where it stays today.

I think of Shukria now and then, and hope that I never go to the BBC website and see that she is the latest woman to be shot by the bastards now ruling Afghanistan again. She fled Afghanistan last August 23, seven days after the Taliban took power. Here is an account from her.

Note: fleeing Afghanistan does not necessarily mean she cannot be shot by the bastards now ruling Afghanistan again.

This is the piece I wrote. There’s a whole newsletter to be written about the ethics of helicoptering in to an unknown place and having the arrogance to think you can understand anything about it, but that will keep. I talked to women and they talked to me and I wrote up what they told me and I hope I did them justice and I hope they’re all still alive and safe.

Animal hero of the week: Jack Cavell

I didn’t mean to present you with another stuffed dog but then I read about Jack and, well, sorry but not.

Stuffed

Jack is made of fur (dog), wood (base), glass (whole), keratin (whole) and leather (whole). He currently stays at the Imperial War Museum in London, where his catalogue heading is “Stuffed Dog, ‘Jack’”, although Jack was more familiar with Belgium than with SE1. Jack belonged to Edith Cavell, a British nurse. Cavell was born in 1865 in Kent, and became a nurse after nursing her father. When the First World War began, Cavell was running a school for nurses in Brussels, and she was very good at it. She had two dogs: Jack and Don.

When war started, her nursing school became a Red Cross hospital. Cavell thought her nursing vocation meant she had to tend wounded of any kind: German, British, French, Belgian, whoever. This did not save her.

The Germans soon invaded Belgium; most of the nurses left but Cavell stayed. That autumn, two British soldiers arrived at the hospital, trying to get home, and they were sheltered there for two weeks. Soon Cavell was involved in an organized underground escape route, and within a year had helped 200 allied soldiers escape. Often, Jack and Don accompanied Cavell and whichever soldiers she was helping, as they walked to meet the guides who would take them on the next stage of their escape. But in the summer of 1915, a collaborator arrived and was helped, and soon Cavell and others were arrested. Cavell confessed, was held for ten weeks in a cell, then executed by firing squad. The Reverend Stirling, a friend of hers, visited her the night before her execution and found her “perfectly calm and resigned.” She said, “I have no fear nor shrinking; I have seen death so often that it is not strange or fearful to me.”

Under international law, the Germans’ decision to shoot a 40-something woman was legal. But it caused fury and outrage. A recruitment poster, one of many, shouted about her being “murdered by the Huns.”

For more on Cavell, I suggest this site. For a grim and shocking account of her execution, read this from the German pastor who accompanied her to the Tir National (“National Shot”) . It features the delightful comment from the military judge to the execution squad that “it was hard for them to fire at a woman, but he wished to impress upon them that she was not a mother.”

But what about Jack? He survived (Don died before his mistress). He was rescued by the Princess de Croy, whose family had also sheltered escaping allied soldiers (the underground password was Yorc, her surname backwards), and lived on a Belgian country estate until 1923. But he missed his mistress, and people said he howled for her after her death. I accept he wasn’t as heroic as Simon or Stubby: he didn’t root out German spies with his teeth or kill a massive rations-stealing mouse named after Chairman Mao. But he accompanied his brave mistress on what were probably quite terrifying walks, and he probably helped calm her fears and for that he is heroic, as was she.

As for how Jack got to be stuffed and end up in the Imperial War Museum, I have no idea and the internet can’t tell me.

Fell running news

I ran a big race and for the first time in many months, perhaps a whole year, I felt good. I attribute that to the fact that I had a B12 shot on the Wednesday. A running friend had told me she had had one and that she felt much better when she exercised. I was feeling so drained and depleted on Wednesday, I impulsively booked an appointment, paid £35 and got injected on the second floor of Harvey Nichols, just beyond women’s glittery and highly expensive fashion.

By the Friday, I was googling, “B12 shot no effect,” but then on Saturday morning at 8am I set off running on the 21-mile Hebden 22 (I don’t know where the extra mile came from), and BOOM. I’ve been on long moorland runs recently and felt so unwieldy and sluggish, they were rarely fun. Mostly, they felt like a physical slog. But the Hebden 22 was so different. I didn’t run faster, I just ran more. Many times, my legs set off running almost without me thinking them into action. And I only felt like it was a slog after about 17 miles, when my knee started to be furiously painful (inflamed ITB, probably), and I had a brief energy slump. But I kept running, and I kept running, and it never felt particularly hard. The joy of running and feeling like everything is working, and you are strong and powerful and can keep going: that is worth £35 even if I have paid £35 for a placebo effect. I don’t think it was though. There must be a reason B12 shots are known in macho cycling circles as “poor man’s EPO.”

This weekend I’m doing the 19-mile Wadsworth Trog, once again in the Calder Valley. It is a race nicknamed "The Beast,” not because of its length or even the elevation (under 4,000 feet), but because of the bogs and the thigh-high tussocks, and the entirely unpredictable weather. It could be a glorious day, it could be a claggy blizzard. If I felt as good as I did on Saturday, I won’t mind what the weather throws at me.

I'm not sure if he's on display or shoved in the Stuffed Dog Department but let me know if you meet him.

I’m not sure why I am feeling sorry for Jack, but I am. Something about him tells me he does not want to be forced to sit in perpetuity!