A bit of a buffet this week, to reflect the inside of my head. My HRT has gone awry after years of being fine. Suddenly I’m sleeping poorly and on days where I put on new oestrogen patches, which I could always guarantee were good mood days, I have felt awful. So. Menopause. The gift that keeps smacking you in the face.

But rather than bang on about that, I’ll introduce you to George Merryweather.

George Merryweather was a family doctor in Whitby, north Yorkshire. I wrote about Dr Merryweather because of his conviction that leeches could forecast the weather.

In a long submission to the Whitby Literary and Philosophical Society in 1851, Merryweather set out his startling claim: that a leech could feel weather, and that many leeches could predict it.76 This barometer ability of the leech had been reported anecdotally before. The eighteenth- century poet William Cowper wrote to his cousin of a storm and of “a leech in a bottle that foretells all these prodigies and convulsions of nature. [. . .] No change of weather surprises him, and that in point of the earliest and most accurate intelligence, he is worth all the barom- eters in the world.”

A man of true pragmatism, he invented a leech barometer — the Tempest Prognosticator — that featured 12 leeches, each in a pint-size clear glass bottle.

He took care that they could see one another, because he thought leeches could get lonely. He called them his “jury of philosophical counsellors” and “my little comrades.”

I admired Dr Merryweather for this (although the barometer did not catch on because the mechanical barometer was less troublesome and did not require live animals to operate). But I also like him for his love of weather forecasting and his profoundly held belief that other people needed to love it as much as he did. He thought, rightly, that it saved lives. The target of his forecasting generosity was always the Whitby Literary and Philosophical Society, which is still in existence and now based at Whitby Museum (but has no record of Dr Merryweather’s epistolary pestering about approaching weather).

He believed powerfully in the power of his leeches, and wanted to share their skills. Yet there is a constant tone of apology in his submissions to the Society that he must predict yet another storm, though the sky was blue. “I am sorry to interfere with your engagements this beautiful weather,” he wrote in February 1850. “I do not trouble you with a little blustering of the wind.”

No. 8. Whitby, February 25th. 8 p.m.

Although I addressed you this morning, I feel at

present authorized to intimate to you the approach of a storm ;

notwithstanding I do so on such a beautiful, serene, moonlight

night.

George Merryweather, M.D. No. 9. Whitby, March 23rd, 1850.

Saturday Afternoon.

My last letter to you was dated on Monday evening,

8 p.m., the 25th ultimo. On the Thursday afternoon following,

the sea was of glassy smoothness, but the wind set-in the same

night, and although lulled during Friday, it stormed during the

night, and also on Saturday night.

I beg to observe, that it is worthy of notice that I have not

troubled you for nearly a month, for which I do not think you

can find cause to call me to account.

On Thursday night, after the committee meeting, I had strong

indications of an approaching storm. As I found I should be too

late to get a letter into the post for you, stamped with that day’s

date, I made up my mind to satisfy you with the evidence of an

individual, to whom I made the communication immediately after

T had made my observations. This storm commenced last night,

and is still raging. I wonder at his urgency. Surely the men of the Philosophical Society could look out of their windows? But Dr Merryweather was a predictor, and he was Cassandra because his writings convey that no-one took him seriously.

No. 10. Whitby, March 30th, 1850.

Saturday Evening.

In consequence of the present storm, you will be sur-

prised at not hearing from me. On Thursday, at 5 p.m., I had

the best signals I have met with indicating a storm ; but owing to

my mind and attention being so much occupied with my profes-

sional engagements, I did not write to you. I trust, however, I

shall hereafter satisfy you, that no storm can escape me without

my possessing a previous knowledge of its approach.

George Merry weather, M.D.

No. 12. Whitby, April 16th, 1850. 8 a. m.

Ox Wednesday, the 3rd instant, H)l p.m., I intimated

to you an approaching storm, which commenced from the N.W.,

on the Thursday night following, and wrecked a ship between

the Piers.

At half-past ten o’clock last night, I had indications of a gale

or storm. Although this morning is so mild and beautiful, I must

do my duty.

George Merryweather, M.D.

I probably can’t adequately convey my pleasure at Dr Merryweather’s persistence. Maybe he was just another old crank tediously claiming he had solved quantum theory or something, to a bored audience of tutting men with whiskers. But the kindness in his essay — which you can read, endless pages of it, here — is charming. And I like to imagine him in a house on a clifftop in Whitby, staring out to sea and reading the water and the wind, checking now and then on his leech comrades, then picking up another sheet of paper and starting another letter.

There is something smart and clever to be said about him having that surname but I can’t think of it.

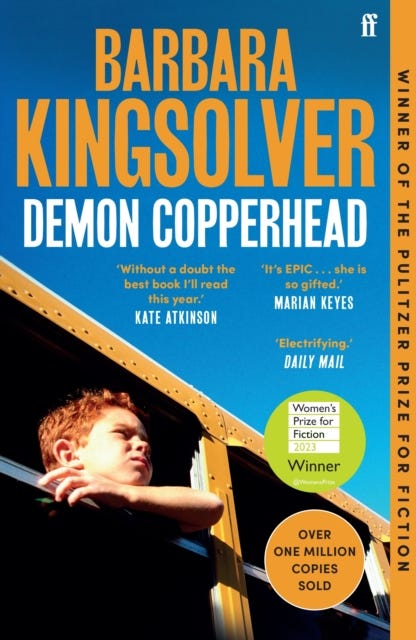

A book

I have just finished reading Demon Copperhead by Barbara Kingsolver. I usually read crime fiction for pleasure, because I spend my days reading journal articles that contain sections like this:

No, me neither.

So before I sleep, I want to escape. But I get weary of crime fiction and every so often I resolve to read other literature. (I first wrote “proper” but I object to genre snobbery and think crime fiction is literature, at least the good stuff, so I checked myself.) I read Birnam Wood and was unmoved. I can’t remember how I found my way to Demon Copperhead, but I still remember Barbara Kingsolver’s book about monarch butterflies (at least, I remember the butterflies), so I bought a sample, started reading and then was so desperate to keep reading, I didn’t buy a printed copy though I’d intended to, but carried on with Kindle. And I have been captivated all week, and anxious to return to the book with the same urgency I usually feel with page-turning crime fiction or thrillers. But it is not page-turning that captivated me in Demon Copperhead. It wasn’t the plot that drew me back. It was Demon’s voice. I didn’t note quotes and I will have to read it again, but my book review is this: I loved it so much and found it so extraordinarily brilliant and gorgeous and revelatory, that when I had finished it I wished I had never read it so I could read it all over again. And that is my highest of highest praise.

Admission: I have never read Dickens. I apologise. I will make that untrue. So I had no idea that Demon Copperhead was a re-telling of David Copperfield, an Oxycontin Appalachian version, and I’m glad about that because I didn’t spend my time spotting how each Copperfield character had been changed in Copperhead. Instead I just delighted in it. Buy it.

Animal hero of the week : Willie

Quaker parrots are known to be chatty. Someone must have had fun making that their name. Willie the Quaker parrot lived in Denver, Colorado in a house shared by Samantha Kuusk, Meagan Howard and Samantha’s two-year-old daughter Hannah.

Willie was clever. He could mimic humans kissing, he could whistle, his impression of a chicken was pretty good.

Then:

One day in 2006, with Samantha at school, Hannah had perched herself in front of morning cartoons while Meagan fussed in the kitchen, preparing the little girl her favorite breakfast treat, a Pop-Tart. When the toaster spit out the pastry, Meagan placed it at the center of the kitchen table to cool. She peeked at Hannah and, confident the child was fully engaged with the TV, slipped out quickly to use the bathroom.

Next, Meagan heard Willie going nuts. Squawking, screeching and also speaking.

She heard two very distinct words from the parrot’s mouth.

Mama. Baby.

Repeated over and over again. “Mama! Baby! Mama! Baby!”

When she rushed into the kitchen, she found Hannah choking on the Pop-Tart. She did a Heimlich maneouvre, Hannah was saved, and Willie has never said the words “Mama baby” together ever since.

Quotes from this piece.

I like this story because when I was six, the same year our father died, I had been to a Christmas party at my primary school and was in our living room wearing a long dress and thick tights. It was 1975 so the dress was probably polyester or nylon or both. I leaned over to stroke the cat who was lying in front of the gas fire, and my dress went between the grill and caught fire. I didn’t notice and walked over to the table on the other side of the room. My brother was 8, probably, and saw I was on fire. We were a troublesome pair of siblings, always yelling at each other (but now we’re really close), so at first my mother, who was in the kitchen talking to an insurance man, thought it was the usual fighting. Then she thought it sounded different. She rushed into the room to find me fully on fire and my brother trying to bat out the flames with his hands.

I was fine. I mean, burned, but fine. I have no scars. I remember the GP carefully cutting off my white tights with scissors. I remember my mother telling me that the GP had told her that had I been on fire for much longer, my hair would have caught and I’d be dead.

So. Get yourself an heroic elder brother and a mother who can tell one yell from another, or a parrot.