One trench or two?

Mining my archives

From 2006

The Trans-Siberian milk train takes a long time to get from Moscow to Siberia. It is called the milk train because it calls at most stations. We never saw any milk.

We had done one day of four days of fourth-class carriage life, and we – 70 or so do-gooding volunteers on Operation Raleigh heading for Irkutsk – were bored. The view was always trees. The food was dull. Our carriage was minimal: bunks covered in blue plastic, sometimes also featuring cockroaches. There was a fierce woman called Valentina who lived in a cupboard between carriages and controlled the hot-water boiler — the samovar — but she was terrifying.

Then we met the conscripts. Two carriages down, still in fourth class – though it may have been third and a half – were two carriages full of young Russian boys-to-men, heading for Chita, three days beyond Irkutsk, to do a couple of years of military service that would make the train look unbearably exciting. We made friends with them and their vodka. We learned that Valentina, when she wasn't feeling dragon-like, sold vodka from her cupboard for 1000 roubles, or nearly nothing. We got drunk, we played cards, we tried each other's languages. And then they got their kit off. We can sell you, they said. It was only a couple of years after the Soviet Union had crumbled. Their caps and belts and shirts and trousers were, for them, the symbol of two years of impending hell. To us, they were hip. The red stars and green caps; the badges and the Cyrillic. It was all so Smiley's people. So unknown. So chic.

Communist chic kitsch had only really been available to gawping westerners for two years, and here was an entire department store of the stuff, for a pittance.

The commerce lasted a day or so. Then one conscript – Yuri? Sergei? The names are all vodka – arrived during a transaction. He was angry. "You should be ashamed," he told his conscripts. "You are selling off your uniforms for money?" He looked at us. "You should be ashamed too."

The selling stopped. I still have my Red Army belt and cap, but they never emerge from the drawer. I've not forgotten being chastised by a conscript, but the chastisement didn't last.

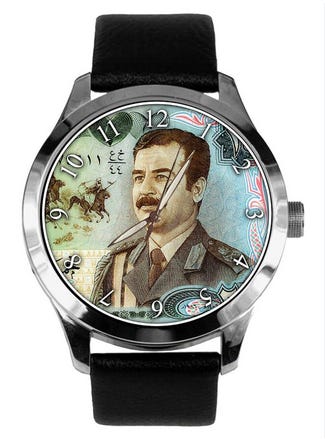

Yuri/Sergei was a proud man. He was angry at the dismantling of his country in about five minutes, and he thought that selling it to these noisy westerners showed a lack of pride. He's probably an oligarch by now. Eight years later, though I remembered Yuri/Sergei's anger, I did it again. In Saddam's Iraq, in 2001, images of the man were everywhere. You couldn't move for seeing the jowly face and the black moustache. His face was on the hotel receptionist's desk; on posters in every shop; on watches and pens and books. I succumbed. I bought six Saddam watches, a few Saddam posters, and a collection of Saddam's books, including his masterpiece, "One Trench or Two." When I returned, friends were desperate for the watches. They thought they were fashionable. They thought – and I didn't disagree – that a homicidal dictator whose son reportedly had people mauled to death with attack dogs, who kept 8 million people on an emotional spectrum that began with dread and ended with terror was comical. His bushy black moustache. His hilarious speeches. His face on a watch! It was all so cute.

But this year something odd happened. Maybe I grew up. Maybe it was penance for having turned the iconic symbols of monstrous regimes into fashion. Maybe it was China.

This summer I went to China for the first time. For a while, I did what first-time visitors all probably do. I marvelled at how good the food was there, and how crap it was here. I noted down the hilarious Chinglish. I goggled at the smog and the thoughtless relentless construction. But I never, ever, bought any commie kitsch.

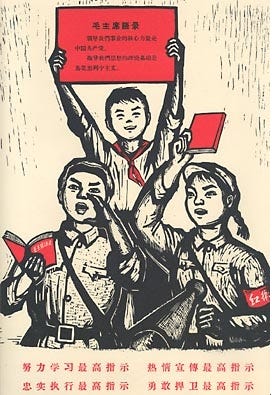

It was everywhere. In tourist "villages" from Chongqing to Beijing, there were Mao posters, badges, pens. There were kiosks selling nothing but Little Red Books. There were figurines of teachers and intellectuals being tortured and humiliated – forced to crawl on their knees with placards round their necks – as they had done during the Cultural Revolution. Toy teachers with toy tormentors. In the tourist crafts market in Beijing, the lo wei – foreigners – were rapt. They bought everything. And I felt different. I bought nothing.

In East Germany, nostalgia for communist days is pervasive enough to have a name. Ostalgie, or nostalgia for the East. There are ostalgie discos. There was a globally famous film – Goodbye Lenin – which saw nothing wrong in laughing at the past.

But it's such a recent past. In the Stasi museum in the former east Berlin, the perfectly preserved 1960s furniture, Honecker's bathroom and phone are all interesting enough. But upstairs, in the Stasi library, people still go to find their file and map out exactly how their life was derailed or disintegrated.

In China, it's not even about the past being recent. The past isn't the past yet. Mao is dead, of course. Though his portrait still hangs in Tiananmen, he can be publicly criticised for the failed Great Leap Forward, which caused 30 million Chinese to die of hunger, even if his wife and her fellow three in the Gang of Four took the blame for the Cultural Revolution. The less observant visitor, and the stubborn expat, can even claim that China now has a free market economy, that the police never interfere with citizens unless they break the law, that – a common expat refrain – "I feel freer in China than I ever did in Berlin/London/Chingford."

But the BBC magically goes black whenever anything "negative" about China comes on. A segment about blogging? ZAP. "And now we go to the protests over the new China-Tibet railZAP." There is no Wikipedia. During the month I was there, two reputable journalists were imprisoned for spuriousness. A blind lawyer who defends people trying not to be forced to have abortions was arrested for turning up at court. The Little Red Book is still everywhere, even if it's now got a Gucci cover. And I won't buy it. On reflection, I won't buy Saddam or Stalin either. I've got over it. The icons of homicidal dictators and their murderous regimes have lost their charm. I'd say they should be banned, but that's a bit communist.

More good writing - and from the long ago, too.

I have a ghadaffi t-shirt and feel ambivalent about it: 'hey, look at me - I've got a ghadaffi t-shirt!' vs 'he was a right that - throw the t-shirt away'