They are less fidgety

On space and fury

The Fall

My mother: “But why do you DO it?”

It was a reasonable question. I had just shown her the state of my leg, after I had fallen on it the day before while out on the moors. I hadn’t fallen on a particularly tricky section: as surfaces go, it was relatively easy. A rocky gravel track. But my foot clipped a rock, and unlike the countless times that my foot has clipped a rock and I’ve saved myself, this time I fell forward. Arse over tit, face-planting. That would be bad enough but because I had been running, once I fell the momentum kept me going. My leg and hand scraped along the ground, leaving me with a mighty abrasion and a seriously sore leg. My partner became medic. Stay down, he said. Take your time. Get used to the shock. There was a small beck nearby, so I washed my leg of the blood. And because this is what we do, us fell runners, I set off again. Walking first, then running. And I ran nine miles on my battered leg, because moving it felt better than stopping. When I stopped, it stiffened. When I ran, I mostly forgot about it. The only problem was the heather: it was often just the right height to brush against my bleeding sore skin so that my runing was often yelping and running. But I carried on, and I declined the two escape route options that my partner offered. I felt OK. My partner told me to stand on a rock and show off my injured leg, so I did.

It doesn’t look bad in that image so here’s one from later on:

At the trig on Beamsley Beacon, a kind woman asked me if I was OK and whether I had disinfected my leg. I told her I had washed it in a beck which was probably full of sheep-shit. That is the fell-runner’s disinfectant. Bravado aside, when I got home I carefully washed it, and remembering the severely infected graze I once got, plus the blood poisoning, I tweezered out every tiny piece of grit. That was fun.

The next two days consisted of me wondering how the hell I’d run nine miles on a leg that was now stiff and sore and so troublesome, I almost got my walking poles out. So, why do I do it?

These are a few of the things that have happened since I started running at the age of 41.

post-tibial tendonitis

inflamed achilles

inflamed high hamstring tendon (twice)

weird knee thing (probably fascia)

infected fall-related graze (infected because of sheep shit and muck)

plantar fascitis

I’m sure there’s more. I won’t add up how much I have spent on orthotics and physio and massages and devices and Savlon, but it’s a lot. For a runner, if something is wrong with the body but not serious, it’s a “niggle.” You can run with niggles. Worse than that and it’s an “injury,” although not in the way that a combat medic would understand that word. Our injuries are hidden. They are in the tendons and muscles and connectors and bones. They are for most people part of the sport. At any time, I can name half a dozen running friends who have either niggles or injuries.

And so, why do I DO it?

Because my body is stronger overall. Because yesterday I had an HRT review at the GP surgery and the GP looked at me and said, “You’re slim and fit and your cardiac risk is low, I’m not concerned.” (I look at the picture of me above and think I am not slim at all and all I can see is too many biscuits.)

Because I can run for miles and endure better than I ever could.

Because I have club-mates and friends who understand the fire-bright joy of running as fast as you can downhill.

Because although I fall (though the latest one is the first one for a long time), usually I bounce. Once I fell and my friend Louise said with wonder, “that was an actual commando roll.”

Because of this:

And because of this:

And that — the space, the air, the sky, the silence, the heather, the rocks, the grit, the views, the freedom, the red kites, the disgruntled grouse, the simple delight of moving through the landscape and keeping going — is why I do it.

Fury

I had reason to be very angry last week. Someone did me wrong and there was nothing I could do about it. I wish I could be more specific but I can’t. The person who did me wrong did so because of ego, and I found that very hard to take. There was just no need for it. So I had a lot of anger and I didn’t know how to get rid of it. It wrecked my concentration and then I was angry about that too. I waited it out and now it is a simmering thing that wakes up when I see this person’s name (this person is a public figure of sorts). Tips for dealing with anger very welcome. Not boxing. I know about boxing. I know, go for a run?

Bric a bobs

They are putting windows in people’s skulls.

Animal hero of the week : Patricia

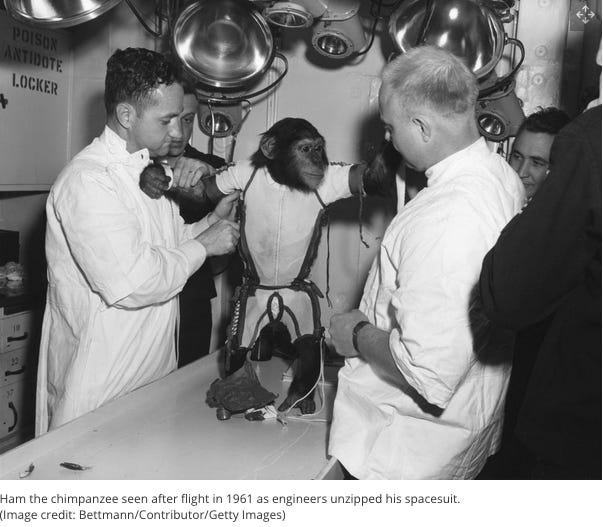

Patricia was a Philippines monkey. On May 22, 1952, Patricia and another Philippines monkey named Mike were strapped into the nose section of an Aerobee rocket. Patricia was seated; Mike was laid down. The boffins wanted to know whether this would make a difference. Then they were sent 36 miles into the sky at a speed of 2000mph.

They had company. Mildred and Albert were two white mice who also made the trip, whether they wanted to or not.

From NASA:

Mildred and Albert were inside a slowly rotating drum where they could "float" during the period of weightlessness. The section containing the animals was recovered safely from the upper atmosphere by parachute. Patricia died of natural causes about two years later and Mike died in 1967, both at the National Zoological Park in Washington, DC.

NASA does not record what happened to Mildred and Albert. Nor does it record what NASA learned from strapping these monkeys in and firing them into space. Space labs used animals because it was thought that humans would not survive weightlessness. But then what? Either the animals died, which they did before Patricia and Mike survived. Monkey after monkey died “on impact.” Take Albert IV, the “payload” on a flight in 1949 on a V2 rocket.

It was a successful flight, with no ill effects on the monkey until impact, when it died.

No ill effects except extinction.

The Soviets were following suit. They used “one-way” animals, a charming concept. Rabbits, mice, monkeys and of course dogs. Why dogs? They were thought to be “less fidgety” than monkeys. Also, “they chose females because of the relative ease of controlling waste.”

Huh? Female dogs poo less than male dogs? Someone enlighten me please.

We’ve all heard of Laika, the most famous space dog. I didn’t know her real name as Kudryavka (Little Curly), or that Americans called her “Muttnik.” But Laika was only the most famous. Before her:

On August 15, 1951, Dezik and Tsygan ("Gypsy") were launched. These two were the first canine suborbital astronauts. They were successfully retrieved. In early September 1951, Dezik and Lisa were launched. This second early Russian dog flight was unsuccessful. The dogs died but a data recorder survived. Korolev was devastated by the loss of these dogs. Shortly afterwards, Smelaya ("Bold") and Malyshka ("Little One") were launched. Smelaya ran off the day before the launch. The crew was worried that wolves that lived nearby would eat her. She returned a day later and the test flight resumed successfully. The fourth test launch was a failure, with two dog fatalities. However, in the same month, the fifth test launch of two dogs was successful. On September 15, 1951, the sixth of the two-dog launches occurred. One of the two dogs, Bobik, escaped and a replacement was found near the local canteen. She was a mutt, given the name ZIB, the Russian acronym for "Substitute for Missing Dog Bobik." The two dogs reached 100 kilometers and returned successfully. Other dogs associated with this series of flights included Albina ("Whitey"), Dymka ("Smoky"), Modnista ("Fashionable"), and Kozyavka ("Gnat").

Of course we know better now than to send innocent animals into space, right? But why should the space people not do what earth people still do to animals in their millions? In 1998, NASA set a “biological payload record,” when more than 2,000 creatures joined the crew of Columbia (STS-90).

A biological payload record was set on April 17, 1998, when over two thousand creatures joined the seven-member crew of the shuttle Columbia (STS-90) for a sixteen-day mission of intensive neurological testing (NEUROLAB). This included rats, mice, snails, crickets, and two kinds of fish. Read NASA’s summary of the mission and you will think nothing went wrong. The humans had a fine time and came back healthy.

But so many animals died, the mission was renamed Necrolab. 57 of 96 newborn rats died. Apparently the baby rats “had trouble floating back to their mothers.” They were not the only casualties:

All but 25 of 225 swordtail fish onboard perished when temperatures inside their specialized aquarium become too high. An air-intake line seems to have become clogged, perhaps because the busy astronauts were unable to clean it as often as required. Less than half the expected number of snail eggs hatched in orbit, and two of four adult oyster toadfish were dead on arrival back on Earth.

The scientists made do, sharing body parts and tissue samples to do their research. Thank goodness for that.